Written

in 1980, with the serious collector in mind, this book notes all the

species then known to have been collected within 50 kilometers of the Nation's

Capital. Focus is on localities. Emphasized are the most significant localities

that were accessible at the time of publication. Scores of additional

localities, a total of 191, are also mentioned, their locations numbered on two

of the maps.

Thursday, July 24, 2025

A LINK TO "MINERALS OF THE WASHINGTON, D.C. AREA IS AVAILABLE

Saturday, December 4, 2021

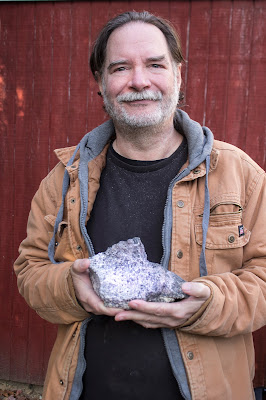

Stuart Herring: Maryland's Most Prolific Field Collector

In the image

above, the specimen he holds is ore quality black chromite coated with violet colored chromian clinochlore (aka kammererite, rhodochrome, penninite) and white talc. He collected it at Bare Hills in Baltimore County. Until he uncovered this and other similar specimens, such material had not been collected in the area for nearly a century. The find is one of Maryland's most significant in the past 50 years.

Field collecting in Maryland has become immensely challenging. Localities that once yielded specimens have given way to sprawl. Strictly enforced laws prohibit collecting in state parks and national parks. Other sites are on private property that effectively forbid trespassing. Most of the few quarries that formerly allowed once a year visits from properly insured mineral societies now proclaim that liability issues prevent them from doing so.

How is it that Stuart is able to devote a major portion of his time to successfully collecting mineral specimens in and near his home state? He focuses much of his approach on rediscovering long forgotten localities, many of them no longer believed to exist.

Plenty has been published during the past two centuries regarding Maryland localities that at different periods were known to have yielded a variety of mineral species. Over time, most of these localities have been built over or otherwise become inaccessible or forgotten. Most of what was written about them appeared in a variety of publications that became obscure, some nearly impossible to obtain, until several years ago. Finally, the Internet came to the rescue.

Minerals of Maryland by Charles Ostrander and Walter Price was one such publication that in its day, many considered a "Bible" for such information. It named and briedly described by county most of Maryland's known localities and listed all the mineral species reported from each one. The Natural History Society of Maryland, which published it in 1940, made Minerals of Maryland available on line just three years ago.

Nearly as recently, Maryland Geological Survey similarly brought on line more extensive and specific information about the localities noted in Minerals of Maryland and added additional ones. Some of the varied publications provide maps that make finding these localities easier.

Lidar data in LAS files, especially when accessed with Arc Gis, has provided collectors with an additional tool for seeking out localities. The technology provides collectors with a description of the earth contours throughout the vicinities where the localities---if any traces of them still exist--- appear on the maps.

Such wonderful tools will only prove helpful to collectors with the knowledge to identify specific species as well as how to search for any that remain. Such knowledge combined with Stuart's extensive collecting experience and the time he has available to collect give him his edge. It helps that he earns a substantial portion of his livelihood as a mineral dealer.

In past posts, Mineral Bliss has feautred several finds Stuart has brought to light. They are as follows:

The Carroll Mine in Carroll County, Maryland

New Finds: Falls Road Corridor Near Baltimore City Line

The Garnets of Stony Run in Baltimore City

Stuart very likely has had more experience collecting at the Mineral Hill Mine in Carroll County than anyone else alive today. One of his proudest finds from the immediate vicinity of this iron and later copper mining operation dating from the 17th Century is pictured at left. The specimen bears silvery carrollite-siegenite with golden chalcopyrite in magnetite. The carrollite-siegenite portion measures to nearly an inch, which is considerably larger than the vast majority of the eponymous Carroll County carrollite examples curently known to exist. Stuart's most spectacular find in our opinion was the deposit of ore quality chromite with chromian clinochlore from Bare Hills in Baltimore County that he holds in our title picture.

Wednesday, November 3, 2021

Peter Via Collection for Grand Reopening of JMU Mineral Museum

It is a

special event when a sizable group of mineral collectors gathers to be the

first to view a large selection of world class minerals. Recently attracting such a crowd was the former

Peter Via collection, which had recently been appraised $16,800,000. Upon his

death, he had bequeathed it to the James Madison University Mineral Museum in

Harrisonburg, Virginia,.

The

collection had never left Mr. Via's private home in Roanoke until he died in

2018. It was the largest gift the University ever received. Because of Covid, a

grand reopening event by invitation only at the museum’s new home had to be

rescheduled from April, 2020 to October 29, 2021.

The crowd

poured in to the Lower Drum of JMU's modern Festival Conference and Student

Center on its East Campus. With leaves approaching peak color, it was a prime time

of year to be in the area. Torrential rain and westbound traffic backed up for

numerous miles on I-81 West were less cooperative.

Notwithstanding,

the number of mineral aficionados that managed to attend the event was

substantial. After a short walk from easy parking, guests wound their way

downstairs to a large visitor-filled room where volunteers at a check- in table

handed out pre-printed tags. Penned onto each was a number referring to the

group with which the holder could enter the museum. Wine and a few snacks were

available to everyone. Down a short hallway, a designated group stood waiting

to enter the exhibit room entrance after a previous group had exited.

Unlike

others who were present, this writer had by special arrangement been able to

visit Mr. Via at his home in Roanoke

years before to see this amazing collection. I had photographed as many

specimens as time allowed and also enjoyed an opportunity to chat with Mr. Via in his den about his mineral collecting

philosophy.

Mineral Bliss's October 27, 2014 post, “Unbelievable but True

The World Class Personal Collection of Peter Via" resulted from that visit.

Subsequently, Dr. Lance Kearns, JMU's Emeritus Professor of Geology and Curator

of the Museum, with his wife Cindy, a current geology professor at JMU, spent time

with Mr. Via during the period when he decided to bequeath his collection to the

university.

When it

arrived, the world famous mineral photographer Jeff Scovil went to work with his camera. Also involved

was Wendell Wilson, the Publisher and Editor in Chief of MIneralogical Record. He personally

authored a 23 page article about the collection that appeared in that

publication’s September-October 2020 edition. At present, numerous images of the

specimens are available on line in association with a brief video narrated by

Dr. Kearns.

Lance and

Cindy Kearns were immediately inside the museum door as guests entered. When I

greeted Lance, he mentioned that Mineral

Bliss’s 2014 post had prompted the discussions leading to the bequest of

this amazing collection to James Madison University.

The

specimens intermingle with the larger collection that Dr.. Kearns describes as

"a composite of five collections." Prior to owning the Via specimens,

JMU had always displayed specimens in systematic suites based on chemical

composition and atomic structure. While the systematic arrangement remains

largely in place, many of the Via specimens are arranged in different kinds of

small groups, especially when based on visual qualities of a given species or

genre. In addition to specimens on display, JMU owns 1770 catalogued specimens

in storage. Some will undoubtedly be candidates for rotation into the display.

Thursday, October 22, 2020

A HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL VIRTUAL 2020 DESAUTELS MICROMOUNT SYMPOSIUM

Though assembled via Zoom because of Covid-19, the 64th annual Desautels International Micromount Symposium from Baltimore, Maryland, was a huge success. Chaired for the eighth time by Dr. Michael Seeds of Lancaster, Pennsylvania on behalf of the Baltimore Mineral Society, it happened October 10, 2020, at 1 PM Eastern Time.

Despite the absence of both dealers and live minerals, this

virtual Symposium drew a significantly larger crowd than live symposia of

recent years. Perhaps this could be

expected sans the time and expenses involved in travel to Baltimore from

destinations around the world. More significant was the glorious manner in

which the event executed its intended purposes

After Dr.

Seeds opened with a few pertinent introductions, he turned the proceedings over

to Col. Quintin Wight of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, the symposium’s perennial

master of ceremonies and also the best known micromounter on the planet. The

most definitive part of each year’s Desautels Symposium relates to the

international Micromounters Hall of Fame. Quintin, of course, was one of the 40

per cent of living Hall of Fame members in attendance.

He noted the criteria for selection to the Micromounters Hall of Fame by emphasizing the pre-eminent qualification of being “loudest for longest” within the community of micromounters. Since so many micromounters appear to be quiet people, “loudest” in this context bespeaks volume of involvement in terms of contribution and service to the micromounting niche of the mineralogical community.

Nearly three hours had now passed. It was time for Al Pribula, President of the Baltimore Mineral Society to stage the Society’s annual voice auction. It hardly mattered that the offerings were so much fewer than if the event had been in person. The high level of enthusiasm that had been apparent at the outset had persisted and grown as if to a crescendo. Every minute had grasped the interest of those present, and it made the auction all the more fun.

Sunday, September 27, 2020

George Loud and His Mineral Collection

George houses his collection in an addition to his and Karen's home. It consists of three rooms devoted to mineralogy. One enters into what he refers to as his "man cave," where he is shown sitting with his yellow Labrador Molly. Micromounting materials are evident on many surfaces. The walls bear an assortment of personal as well as mining memorabilia.

The "man cave" leads into a hallway with a mineralogy and mining history library with bookshelves on both sides. They extend from floor to ceiling with a ladder system. Multiple shelves have so many books on Colorado minerals and mineral localities that protruding sheets of card stock divide them according to counties within Colorado.

Beyond the library is the collection room. What first meets the eye is a relatively small single cabinet with minerals from the famous but now off-limits Hunting Hill Quarry in Montgomery County, Maryland. Otherwise, the cabinets are much larger. Keith Williams, who constructed numerous mineral cabinets at the Smithsonian, built most of them.

Specimens displayed in a long row of cabinets lining the left wall begin with a suite from the locality that's closest to where George lived most of his life, the fabled Centreville Quarry in Fairfax County, Virginia. Our title picture shows a few of the specimens. As everyone thereabouts who is interested in minerals knows, this locality has yielded too many world class apophyllite and prehnite specimens for passing judgment as to the best ever. What George's suite accomplishes is to show just how perfect they can get.

Specimens from Amelia County, Virginia are plentiful in an adjacent cabinet. It would be reasonable to conclude that some of the specimens in the image at left could vie for best of species from their specific Amelia County localities. Prominently displayed nearby are several relatively huge specimens with varied matrixes featuring turquoise crystals from the Bishop Copper Prospect in Lynch Station, Campbell County, Virginia.

Provenance is paramount. His labels name as many previous owners as he can ascertain. The ultimate Phoenixville Lead Mining District anglesite specimen from the Wheatley Mine is a good example. Collected between 1855 and 1860, it had eight previous owners going all the way back to the famous mining magnate and mineralogist Charles Wheatley. George also records this same information and other pertinent data about every specimen on index cards accompanied by all previous labels.

The collection boasts many scores of suites and individual specimens beyon the very small fraction of them mentioned herein. Standing out is a sizeable suite of gemmy minerals from Maine, a superb suite from Bisbee, Arizona, and a suite from Franklin and Sterling Hill, New Jersey width a specimen that amazed me of native gold in willemite .

George made a point of showing me a witherite specimen from the Pigeon Roost Mine near Glenwood in Montgomery County, Arkansas It is pictured at left. Clearly one of his favorites, he believes it could be a contender for the best of the species known to exist.

Nearby, a suite from Magnet Cove Arkansas, a favorite collecting spot for George, bears special mention. It includes a crystal of andradite (var.) melanite, which George thinks could be the best of its genre ever collected there.

Another garnet that impressed me nearly as much was prismatic and from North Carolina's Spruce Pine Mining District. Among numerous North Carolina minerals, he also pointed out a crystal of anatase pseudomorph after titanite from Tuxedo Junction at Zirconia in North Carolina's Henderson County.

Sunday, August 16, 2020

PIEMONTITE NEAR CULP RIDGE PENNSYLVANIA AND NOW IN MARYLAND!

Three of us headed from Baltimore in search of piemontite on a hillside near Hamiltonban Township in the South Mountain area of Adams County, Pennsylvania. We parked along Mount Hope Road near Gum Springs Road. If we were going to find piemontite we knew it would occur in outcrops where reddish pink metarhyolite dominated. Soon we were following a trail along the base of the ridge.

Within a few minutes, we spotted some large boulders through the trees. Although no hint of a trail led to them, we bushwhacked about 20 yards uphill, found the reddish pink metarhyolite we were looking for and soon spotted some piemontite. It occurs mostly in adamantine radiated microscopic prisms exclusively at or near where quartz has intruded the metarhyolite. We believe we were in one of six known South Mountain area piemontite localities, at least four of which date from the 1890’s

We were also within about a quarter mile of seriously

overgrown dumps from copper prospects dating back yet further into the 19th

Century. This was one of about 20 known localities for native copper in

the South Mountain area. Always found in volcanic metabasalts, the copper

was from deposits that were much smaller than but otherwise closely resembled the enormous and lucrative

Keeweenaw deposit in upper Michigan. Although extensively prospected well into

the 20th Century, the copper never proved plentiful enough to be

viable.

The South Mountain area has long fascinated geologists. Their focus has always been less on the copper than the geologic history exposed by rocks over hundreds of millions of years

of erosion. Research regarding the piemontite occurrences, while thorough and specific, was limited to separate studies.

This region prominently straddles the Maryland line into

Frederick County, where the geology is similar. The Pennsylvania side calls it

South Mountain, Maryland calls it the Catoctins. Geologists have extensively

studied the rocks on the Maryland side as well. Nearly all the studies, however, have been specifically limited either to Pennsylvania or to

Maryland.

Some of the Pennsylvania studies at least acknowledged the presence of piemontite, even though sometimes referred to as “rusty epidote,” or "piedmontite." In one of a series of articles entitled Chronicles of Central Pennsylvania Mineralogy, the late Jay Lininger described the phenomenon: "Like the comedian Rodney Dangerfield who didn't get no respect." In Maryland, piemontite got less than no respect.It has received no mention.

Yet, piemontite has aesthetic qualities that make it a

highly appealing mineral species as a member of the epidote group, like zoisite

and allanite. John Sinkankas in Gemstones

of North America even listed “piemontite in rhyolite” as “semi-precious gem

cutting material.” Its presence shows less weathering and better luster within freshly broken rock. Though usually in radiating microscopic crystals as described, a few specimens that are less common bear larger crystals up to

about 15 mm. x 3 mm. Nearly all such

crystals have been fractured upon recovery. Seeing perfection is unrealistic. Piemontite is

neither common nor highly valued relative to many other species, but regard for it is rising. .

A few years ago, this writer was working a booth at a show

in the Towson, Maryland Armory. A man walked by with the most spectacular

South Mountain piemontite specimen I’ve ever seen. I’m sure he intended to sell

it, but he did not mention a price. After I complimented the specimen, he moved

on. Had this happened today, I would happily have emptied my wallet.

Nothing short of synchronicity could make sense of how this writer personally collected piemontite in Maryland’s Frederick County only three weeks before our recent collecting trip. I was clueless that piemontite was in a specimen picked up in a field less than a mile down a road leading west from the tiny hamlet of New London.

Three weeks later by sheer coincidence, a collector called

and asked me to join him to look for piemontite in Adams County and write a post

about it if we found any. We went, we

found piemontite, and it was obvious that the material in which we found it was

the same as the piece I’d collected near new London. Doing my research, I read something in the aforementioned article by Jay Lininger that aroused my curiosity. The article stated that that the renowned late

geologist Dr. Florence Bascom, in a her PhD thesis about piemontite, “proved that some of the pink colored rhyolites drew their color

from included piemontite.” I should mention that Dr. Bascom was the

first woman in the United States to earn a PhD in geology and later went on to establish

the Geology Department at Bryn Mawr University.

So I went out to the rock pile in the back yard and grabbed the metarhyolite I’d found near New London. A presence of piemontite was readily apparent. I did not report this as a new find for Maryland because it seemed quite obvious that the specimen was not indigenous to the field where I collected it.

However, metarhyolite has an established presence just

a few miles further west of New London in Maryland’s Catoctins. As long a some of it is the same color as the ubiquitous reddish metarhyolite on the Pennsylvania side of the state line, piemontite will very likely be present., Once uncovered and

verified, it could be a legitimate new find for Maryland.

Wednesday, May 6, 2020

Remnants of Maryland's Historic Patapsco Mine

A collector friend succeeded in locating what appeared to have once been a pit from one of the Patapsco Mines. On the ground nearby, we found lying on the ground several decent magnetite specimens with notable cleavage as well as rocks bearing significant malachite. Also present in a few rocks were very small amounts of epidote, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and bornite. We found no evidence of "carrollite."

A collector friend succeeded in locating what appeared to have once been a pit from one of the Patapsco Mines. On the ground nearby, we found lying on the ground several decent magnetite specimens with notable cleavage as well as rocks bearing significant malachite. Also present in a few rocks were very small amounts of epidote, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and bornite. We found no evidence of "carrollite." After penetrating the surrounding dirt with a garden trowel, we found more that was too dirty to examine on site. The highlight of the day presented itself inside a rock that we broke open. Pictured at right, it appears to be chrysocolla, albeit of a deeper blue color than expected, some of which visually almost visually suggested azurite. The Natural History Society of Maryland's 1940 Minerals of Maryland publication by Ostrander and Price reported both species.

After penetrating the surrounding dirt with a garden trowel, we found more that was too dirty to examine on site. The highlight of the day presented itself inside a rock that we broke open. Pictured at right, it appears to be chrysocolla, albeit of a deeper blue color than expected, some of which visually almost visually suggested azurite. The Natural History Society of Maryland's 1940 Minerals of Maryland publication by Ostrander and Price reported both species.